GILDENBERG, Bernard "Duke" (1925 - 2013)

GILDENBERG, Bernard "Duke" (1925 - 2013)

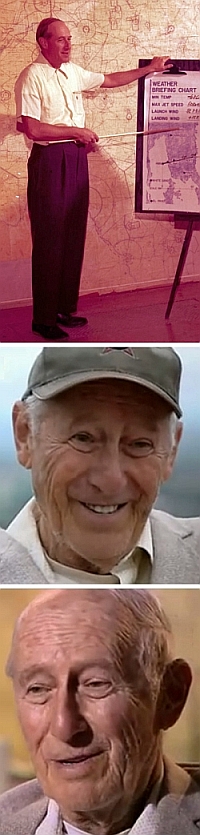

Bernard David Gildenberg, known widely as "Duke," was a meteorologist at the Balloon Branch in Holloman Air Force Base in New Mexico. There he served as Meteorologist, Engineer, and Physical Science Administrator from 1951 until 1981. During this period, Gildenberg, a recognized world expert in upper atmospheric wind patterns, pioneered methods to launch, control, track, and recover high altitude balloons. Many of these methods are still used today by the U.S. Air Force and by research organizations throughout the world.

He was born in Hazleton, Pennsylvania, in 1925 and raised in Brooklyn, New York. He served in the U.S. Air Force during World War II, stationed in the Aleutian Islands of Alaska, where he began his career in meteorology. Before his military service, he had dreams of becoming a journalist and even applied to Collier's magazine at 17. During the war, after being rejected from pilot training due to medical issues, he worked in cryptography, decoding top-secret messages from resistance fighters in Europe and coordinating bomber communications. His early intelligence work gave him a top-secret clearance, and he was involved in meteorological cryptography, exchanging weather data with allies-crucial for wartime flight planning.

Following the war, he studied at New York University's Guggenheim School of Aeronautics, where he met Charlie Moore, a future collaborator on high-altitude balloon projects. After graduation, Duke took a position at the Naval Ordnance Test Station in California and later joined Holloman Air Force Base in New Mexico in 1951, where he remained involved in advanced balloon and aerospace work for decades. He lived in La Luz and Tularosa, New Mexico, for over 60 years and designed his own adobe house on 80 acres near Tularosa.

Gildenberg became a key figure in high-altitude ballooning, contributing to Project Man High and Project Excelsior, both precursors to human spaceflight. He worked closely with pioneers such as Capt. Joe Kittinger, Dr. David Simons, and Col. John Stapp. As a meteorologist, his forecasts were critical, often deciding whether launches could proceed. His reputation was so strong that Kittinger said if Duke gave the thumbs-up, you went; otherwise, you'd think twice. His specialty in wind pattern analysis was so precise he could predict a parachuted object's landing within 100 yards from 100,000 feet.

Duke was briefly considered as a test pilot for Project Man High and passed all the preliminary tests, including claustrophobia, pressure chamber, and parachuting. However, a balloon training accident where he sustained serious spinal and rib injuries disqualified him from flight. He returned to his crucial role as chief meteorologist, providing final launch approvals and forecasting safety-critical conditions. His forecasts played a key role in the success of record-setting missions such as Kittinger's jump from 102,800 feet during Project Excelsior in 1960.

Although he never married (largely due to caring for his ailing parents, especially his father Abe, a World War I veteran who was mustard gassed) Duke had a large extended family, including a brother, sister, and several nieces and nephews. He called himself a "balloonatic" and remained involved in high-altitude research well into retirement. Even after officially retiring in 1981, he continued consulting for the Air Force and NASA, contributing to sensitive re-entry and reconnaissance projects, including Apollo.

In 1982, he provided critical weather forecasting support for Kittinger during the Tropicana Aero Cup, a long-distance balloon race. His strategic holdbacks and precise guidance helped Kittinger achieve a long-distance record, though not the grand prize.

Despite playing a foundational role in American space exploration, Gildenberg remained modest about his contributions. He published scientific papers and appeared in documentaries and films like Man High and The Land of Space and Time. Known for his dry humor, he once joked about the risk of sterility from cosmic radiation exposure, saying as a bachelor, ''that might be a good deal.''

He passed away on April 2, 2013, of natural causes, at the age of 88. As per his wishes, his body was donated to the University of New Mexico Medical School. Throughout his life, he was remembered not only for his professional brilliance but also for his humility, sense of humor, and dedication to both family and science.