North Carolina license plates proclaim their state "First in Flight". Ohio, birthplace of Orville and Wilbur Wright, claims to be the "birthplace of aviation". However, the first flight in North America took place in Philadelphia. Granted, it was a balloon, but Philadelphia can rightfully claim to be the site of the first flight in the United States.

Historical context

Most people know the Montgolfier Brothers made the first hot air balloon flights in France in 1783. Other aeronauts soon followed as their aerial adventures captured the popular imagination. A few intrepid souls became "professional" balloonists; that is, individuals who made their living by performing demonstration flights. The first of these was Jean Pierre Blanchard.

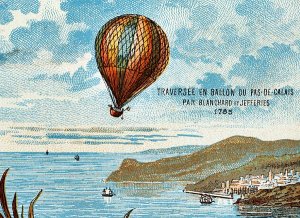

Described as humorless, egotistical, and mean-spirited, Blanchard became infatuated with ballooning after hearing of the Montgolfier's exploits. His other idiosyncrasies aside, Blanchard was very mechanically inclined. While in his teens, he built a four-wheel vehicle he called a velocipede, and a few years after that tried to build a flying machine (which didn't fly.) Within two years of focusing on balloons, he was the world's best known and most widely travelled aeronaut. Blanchard is best remembered for being the first to cross the English Channel by balloon on January 7, 1785. Dr. John Jeffries accompanied him on the flight.

Blanchard performed a number of public ascents around France during 1784. All too frequently, the demonstrations went awry and French audiences became increasingly jaded with Blanchard's exploits (and his personality.) Seeing his audience decline, Blanchard set out for England and fresh patrons. Although the British were first skeptical of this new French invention, Blanchard managed to eke out a living and eventually found a sponsor, Dr. John Jeffries.

Dr. Jeffries was a physician who had been born in Boston. During the American Revolution, he moved to England due to his British sympathies. On November 30, 1784, Blanchard and Jeffries performed a flight for the Prince of Wales and other dignitaries. After their landing, Blanchard and Jeffries began planning what was then a very ambitious and unprecedented project: the first crossing of the English Channel by balloon.

From Dover to France

Jeffries covered the 700-pound expense of the flight in exchange for his being allowed to accompany Blanchard. Not wanting to share in the glory of the voyage, Blanchard reportedly tried to find ways to exclude Jeffries from the flight. A few days before the flight, Blanchard had a tailor sew weights into his vest. While wearing the vest, he planned to declare the balloon was overweight and Jeffries would have to remain behind for the flight to have any chance of success. Jeffries discovered the ruse and demanded his rightful place on the flight.

Blanchard and Jeffries took off from Dover on January 7, 1785, bound for France. Always looking for publicity, Blanchard carried a bundle of leaflets promoting his aeronautical prowess that he planned to scatter over the countryside. At first, their sojourn went well as the wind carried them eastward. Once over the Channel, however, the balloon lost altitude and the pair began tossing ballast overboard to remain aloft. By the time they were two-thirds of the way across, all their ballast was gone, so they began tossing everything in the gondola they possibly could, even their clothes. About two hours after take off, they crossed the French coast clad only in their underwear and the cork life jackets they brought in case they landed in the water. Blanchard and Jeffries continued inland for another half-hour. Blanchard finally brought the balloon to a landing in a small clearing.

Later that year, Blanchard made the first aerial voyages in Germany, Holland, and Belgium; the following year, he made the first flights in Austria, Switzerland, and Poland. Eventually turning his attention to the New World, Blanchard decided to set out for America. Leaving England aboard the ship Ceres on September 30, 1792, he arrived in Philadelphia on December 9. He was received by President George Washington and Pennsylvania Governor General Thomas Mifflin. Blanchard had already made 44 balloon flights in Europe; he proposed to make his 45th in the United States.

The flight

Ever the self promoter, Blanchard planned to sell public subscriptions to finance the flight. The flight was set for 10:00 AM on January 9, 1793. Blanchard sold subscriptions for $5.00, which was quite a bit of money then. He also planned to sell tickets for $2.00 each to witness the launch. Blanchard's goals were to sell 500 of the $5.00 tickets and twice that of the $2.00 admissions. Gate receipts fell far short of expectations and reportedly amounted to only $405.

The City of Philadelphia allowed him to use the yard of the Walnut Street Prison, on the southeast corner of 6th and Walnut Streets. Temperatures on the appointed day were relatively mild for that time of year. At 6:00 AM, Blanchard recorded a temperature of 30o Fahrenheit. Blanchard noted it was up to 35o by 8:00, but the sky was "overcast and hazy". Despite the cloudy skies, he began filling the balloon with hydrogen, or "inflammable air", as he called it. Over the next hour, the clouds dissipated and the sun shone through.

At ten o'clock, the appointed hour, it was 47o with clear skies and a light breeze. President George Washington was there, as was Mr. Ternan, the "Minister Plenipotentiary of France to the United States". Despite his time in England, Blanchard did not speak English. To assist him when he landed, President Washington handed him a "passport" that contained the request that anyone reading the document "oppose no hindrance or molestation to the said Mr. Blanchard".

Finally, all was ready. Blanchard loaded some food, wine, and meteorological instruments into the balloon gondola and prepared to cast off. A cannon report signaled the start of the flight. At first, he hovered a foot off the ground as two men held on to the gondola. Then, he asked them to let go and the balloon took off. As he ascended, Blanchard was "astonished" at the "immense number of people, which covered the open places, the roofs of the houses, the steeples, the streets, and the roads, over which my flight carried me in the free space of the air." He heard their cheers as he passed overhead and headed in a generally southerly direction. Blanchard took a passenger on the flight a small black dog given to him by a friend.

Over the Delaware River, he reached the highest point of the flight; 5,812 feet, as measured with a barometer he carried with him. Blanchard emptied six bottles containing "divers liquors" to collect air samples for a certain Dr. Wistar. He was also asked to note his pulse rate. Blanchard observed it was 92 beats per minute; on the ground it had been no higher than 84. He also attempted to see if the flight had any effect on the magnetic properties of a lodestone he carried.

"I strengthened my stomach with a morsel of biscuit and a glass of wine", as Blanchard later wrote, then decided to land on the New Jersey side of the Delaware River. Opening the valve, he began his descent. At first the balloon was headed toward a densely wooded area, so Blanchard released some ballast to regain altitude. On the third attempt, he finally found a suitable landing spot. Jean Blanchard landed in Deptford Township, New Jersey, at 10:56 AM. He'd traveled about fifteen miles.

Msr. Blanchard released the dog, which ran to drink some water from a nearby pond. A curious observer noted the balloon and came over for a look. At first, he seemed fearful and was about to leave, then Blanchard held up one of his two remaining bottles of wine. Soon, the man was helping him gather the balloon for transport back to Philadelphia. Another person approached, carrying a gun. The first man assured him Blanchard was an "honest man" and had some "excellent wine." Soon, all three were organizing the balloon. More people arrived and before long, the balloon envelope was packed inside the gondola and everything loaded on a carriage. Everyone seemed impressed by the note from President Washington. "How dear the name of Washington is to this people!" he later wrote.

The owner of a nearby house offered Blanchard the use of a horse. Unable to control the animal, he walked to the next house and was offered and a meal of potatoes. Declining food, he wrote out a certificate for his landing that half a dozen local citizens signed. Another, more manageable horse was found. Accompanied by a large group of horsemen, Blanchard rode to a tavern about three miles away. There, he met Mr. Jonathan Penrose, Esquire, who offered Blanchard aa ride in his carriage to the banks of the Delaware River.

After crossing the river, Penrose had another carriage ready and they went to the lawyer's house in Southwark. While Blanchard ate another meal, Penrose arranged to get the balloonist back to Philadelphia.

He arrived at his room around 7:00 PM, the first flight in the new Republic a complete success.

About the author

Gregory P. Kennedy is an internationally known expert in aerospace history. He has authored, co-authored, or edited eight books on space history including Touching Space: The Story of Project Manhigh, which was released by Schiffer Publishing Company of Atglen, Pennsylvania (www.schifferbooks.com).

He has also published numerous articles on the Manhigh project and recently appeared on a PBS documentary entitled "Space Men".

With nearly 40 years' experience in aviation and space museums, Mr. Kennedy has worked at the Smithsonian Institution; the Space Center; American Airlines C. R. Smith Museum; and No. 1 British Flying Training School Museum. While at the Smithsonian, he was Associate Curator for the National Air and Space Museum's collection of manned space flight artifacts.

It was during his tenure at the Smithsonian that he became fascinated with Project Manhigh and the contributions of high-altitude ballooning to space exploration. At the Space Center (currently known as the New Mexico Museum of Space History) in Alamogordo, New Mexico, Mr. Kennedy met many Project Manhigh personnel.